- Home

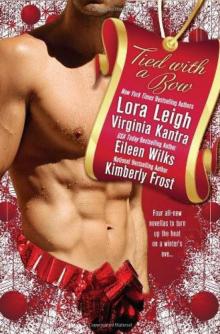

- Eileen Wilks

World of Lupi 10 - Ritual Magic Page 9

World of Lupi 10 - Ritual Magic Read online

Page 9

Julia.

That was a man’s voice, too, but not the same man. She knew this voice. He was really nice and . . .

“Julia, I need you to wake up now.”

She blinked her eyes and everything was bright again. Too bright for eyes barely awake, and she was staring up at a white, white ceiling and someone was holding her hand, so she wasn’t alone, and that felt good, but . . .

“Back with me now?”

She could hear the smile in his voice so she turned her head on the pillow and there he was—the gorgeous man she’d first seen in the hall in the restaurant. The man who was the one good thing in her crumbling life. Mr. Turner. She managed to smile at him, but it felt wobbly.

She remembered some things now, and she didn’t want to.

“You seemed to be having trouble waking up,” he said, and he smoothed her hair back from her face in the way her mother sometimes did. Not her father. Father was as hard to reach as the FBI agent in her dream. Harder, because he never tried to reach back. “Maybe you didn’t want to.”

“No,” she whispered. “It’s okay you woke me up. I had . . . bad dreams.”

He nodded as if he understood, and even though she knew he didn’t, not really, it helped that he wanted to. “That’s not surprising. Julia, we’ve found someone who can help. He can’t make things right, but he can help, if you want him to.”

“What—what’s his name?”

“Sam.”

“Yes,” she said quickly. “Yes, please.”

* * *

IT was after midnight when Lily stepped out of the bright-ly lit emergency room at Scripps Mercy to go to UCSD Medical Center, where Barbara Lennox lay in a coma. Surprise stopped her steps. It had rained while she was inside—not a lot, judging by the dearth of puddles, but enough that the pavement was wet and the world smelled wonderful.

She drew in a lungful of air scrubbed clean, perfumed with ozone and humus. Night air slid like cool silk over the skin on her face. Earlier she’d gotten her shoulder harness and a slightly wrinkled jacket from the trunk of Rule’s car because she was damned if she’d work a case without having her weapon at hand. Now she wanted to take that jacket off and let the clean air wash over more of her. She didn’t; people got jittery if they saw her weapon. But she did suck in more of that crisp air.

Scott made a motion and Mark loped around her. Mark would use his nose to make sure no one had messed with the car while they were inside. “You drive,” she told Scott.

He nodded. “Where are we going?”

“UCSD Medical Center.” Her feet didn’t want to move. She didn’t want to see the woman in a coma. Was that what awaited Lily’s mother if she didn’t allow Sam to help? Why was one victim comatose, another shaken but functional, and a third somewhere in between?

Stupid feet. Those questions wouldn’t get answered by standing here in the parking lot. Lily made herself start for the car.

A wisp of fog drifted in front of her and quickly shaped itself into a man—a hard-faced man with dark hair wearing a dull gray suit with a wrinkled shirt. “It’s Drummond,” she said quickly to Scott, then: “You’d better not wink out right away. I didn’t get to ask you anything, and—”

“Things are different this time.”

“Different how?” She cocked her head. “You look younger.”

“Never mind that shit,” he said, but he ran a hand over his hair—which he had more of than he used to. He looked maybe forty, she thought. Not a lot younger than when he died, but some. The age he’d been before his wife died? “I’ll mostly be working things on my side. I may not even hear you call me like I used to. I’m not tied to you the same way. Because we used to be tied I can find you, but I couldn’t talk to you if not for the way you died once. You didn’t tell me about that.” He scowled as if she’d withheld facts pertinent to a case.

“So who did?”

He waved that away as unimportant. “Someone on this side. The thing is, having died once, you’ve got this little open place in you. It lets me get close enough for you to hear me.”

She scowled. “I am not turning into a medium.”

“Okay, fine. I doubt any ghosts are going to find that spot, anyway. Only reason I can is because of that tie we used to have.”

“But if the tie is gone—”

“It left . . . call it a path. Or a habit. Same difference. Would you quit worrying about the shit I can’t explain and pay attention? It’s a lot harder for me to manifest this time and I can’t do it for long, and there’s stuff you need to know. First, you’re dealing with something Friar got from that elf before he escaped from the warehouse. An artifact.”

“Did you see it? What does it do?”

“I didn’t see it. I felt it. It feels, uh . . . evil, I guess you’d say.”

Lily turned that word over in her mind. “Evil is a pretty broad category.”

“On this side, evil means something specific. Evil affects . . .” His mouth kept moving, but she didn’t hear anything.

“Back up. I lost some of that.”

He scowled. “There’s stuff I can’t say. Not won’t. Can’t. Just take my word for it—what Friar got hold of is evil in a way that upsets the heavy hitters on my side of things.”

“Heavy hitters?”

He looked down and muttered. “Angels. Sort of. Not really, because they aren’t . . . oh, hell, call them whatever you want, or don’t call them anything at all. That might be best. The thing is, everyone on this side is real restricted in what we can do on your side. Even the heavy hitters. It’s all about choice. Choice and time. On your side, time’s like a funnel that lets only one drop of now through at a time, and choice is what you do with that drop. No one gets to take away the choices other people make—only, that object Friar got hold of does just that. I don’t know how it works, so don’t ask, but by wiping out memories, it robs people of all the choices they made.”

Lily thought about her mother. All the choices Julia Yu had made over a lifetime, wiped out. Disintegrated. Her throat tightened. She managed to push a couple of words out through her tight throat. “Yeah. That’s evil.”

He nodded. “It affects this side of things, too. That’s why I can be here. There’s a . . . it’s like a fissure or a crack. A break created by that artifact.”

“But why you?” She waved vaguely. “I mean—there must be lots and lots of dead people who could—”

“Watch who you’re calling dead. I died, sure, but I’m not dead.”

“We’ll talk about terminology another time. Why you?”

He shrugged. “Mostly because I can. Most folks on this side can’t interact with your world at all, but because of the way I died, that tie we used to have, I’ve got a toe in the door. All that death magic stirred things up, plus there’s the way I . . .” His mouth kept moving, but silently.

“You went mute again.”

“Shit. The stuff I can’t say . . . anyway, I’m not as rooted on this side as I’m supposed to be. I could’ve gotten that fixed, but I’m needed for this. I’m small enough that I can slip through that crack to work with you on your side. The heavy hitters can’t. They . . . there’s so much of them, see. They’re part of your world, but it’s just their shine you get, not all of them. They can’t be squeezed into the funnel of time without breaking it.”

“So instead of an angel, I get you.”

He grinned crookedly. “That’s pretty much it.”

“You grinned.”

That brought back the familiar scowl. “What the hell are you talking about?”

“I don’t think I ever saw you grin. Smirk, yes. Grin, no.” She tipped her head. “Did you . . . there at the last, I mean, at the warehouse, you said her name. Just before you poofed out. Sarah. You found her?”

“Yeah.” Softness seeped into his face the way light

seeps into the sky at dawn. “Yeah, I did. I don’t remember much, but I know I found her.”

“You don’t remember? But that—that’s like my mother—”

“No,” he said firmly. “It’s not the same at all. My memories of that other place don’t fit into this place, that’s all. They aren’t gone. They’re sort of packed up, waiting for me.”

A cold hand gripped Lily and squeezed. “Then my mother’s memories are gone. Not damaged or lost. Gone.”

“Not exactly. I mean, they’re gone, but . . .” He ran a hand over his hair. “I can’t explain, mainly because I don’t understand. The idea is to get her back to being herself. To get all of them back to themselves. I don’t know how we do that. I don’t know if that’s something that can even happen on your side of things. Might be the missing pieces can’t be returned to her until she’s on my side.”

“Until she dies, you mean. Even if we do everything right, she may not get her memory back while she’s alive.”

“Yeah. Yeah, that’s what I mean. I know that’s hard to hear, but it’s one possibility. Lily, there’s a lot more affected than your mom. A lot more than you’ve found so far.”

God, could it get any worse? “How many? Who are they?”

“Can’t tell you that. And remember, when I say can’t, that’s exactly what I mean.”

“What can you do?” she cried, frustrated.

“Not much. I can watch your back. I think I’ll know if I get near the object. It has . . . I don’t know what to call it. A spiritual signature or color or . . . see, on this side we use spirit instead of light to see things. Sort of. It isn’t really seeing, but you can think of it that way, and that’s how I’ll know if the artifact is nearby. Otherwise . . . they didn’t exactly give me a training manual, so I don’t know what all I can do. No, wait, there’s one more thing. I should be able to let you know when your saint shows up.”

“My saint? What the hell are you—”

He smirked at her. “You wanted one. Pissed you off that you got me instead.”

“Yes, but—hold on a minute.” Lily’s phone dinged to let her know she had a text. Her heart started pounding. She snatched her phone from her purse.

It was from Rule. She read his message quickly, then read it again. Her shoulders slumped in relief.

“Good news?”

“My mother . . . Julia agreed to let Sam help her. They’re checking her out of the hospital now.”

NINE

THERE were thirty-one hospitals in the Greater San Diego area. By 2:45 A.M. Lily had been to eleven of them and was pulling into the ER parking of hospital twelve. Drummond had accompanied her at first, but after the fourth stop he’d said he had stuff to do “on his side.” He hadn’t explained and she hadn’t seen him since.

Eleven hospitals meant two false alarms and fourteen victims that she’d confirmed by touch. None of them had an obvious connection to the others. Fourteen victims, and they had no idea what they were dealing with or how many more might be out there.

Lily had talked to Ruben again on the way here. He’d decided it was time to wake the president up.

Hospital twelve was City Heights. She’d put it next on her list because it was more or less on her way back to St. Margaret’s, where they had two more possible cases.

Her mother wasn’t at St. Margaret’s anymore. She was at Sam’s lair. Lily had heard from Rule about that. She’d also heard from her father about it. She’d heard him out, then she’d shut what he said out of her mind so she could do the job.

Things get to be clichés by being true over and over. The ER at City Heights Hospital fit every cliché of an inner city emergency room. Even at this hour, it was crowded and noisy. It reeked of disinfectant with a whiff of eau de homeless guy, and the overworked staff got through their shifts on a mix of adrenaline, bad coffee, and black humor. Some were burned out. Some were still fiercely idealistic, though they hid it behind a heavy veil of cynicism.

In other words, it was a lot like a cop shop. Lily felt right at home as she walked up to the nurses’ station. “I’m here to see Festus Liddel,” she told one of the women behind the counter, holding out the folder with her ID.

“Liddel?” The woman’s braids flared as she turned her head sharply. “God, Denise, don’t tell me you called the FBI about Liddel! Plackett is gonna have a cow.”

The other nurse was twenty years younger than the first and at least twenty pounds heavier. She propped her hands on her ample hips. “And why shouldn’t I call them? That’s what that bulletin said to do, isn’t it?”

“Liddel’s memory got washed away by alcohol years ago.”

“This isn’t the same. You know it’s not the same. He doesn’t even sound like himself. And Hardy says—”

“Hardy!” The first woman rolled her eyes. “Now, listen, sweetie, I know you like Hardy—though God knows why. He creeps me out. But—”

“That was a coincidence! He couldn’t have known.”

“I’m not talking about that, though it was pretty damn weird. I’m talking about the way he looks at you. As if . . . well, it creeps me out, that’s all. What are you going to tell Dr. Plackett when he finds out you called this nice agent? You going to explain that Hardy thought we should call in the FBI?”

The second woman giggled. “It would almost be worth it to see his face.”

The first woman sighed and shook her head and looked at Lily. “I’m afraid you got dragged out here for nothing, Special Agent. Festus Liddel is one of our regulars. He can’t remember what day of the week it is most times. Denise thinks his poor, pickled brain is malfunctioning worse than usual tonight, and maybe it is, but that’s not saying much.”

“I’m here, so I might as well see him.” And touch him. That was the quickest way to know for sure if Festus Liddel was victim fifteen.

“I’ll take you to him,” Denise said. “You can see what you think, but he is not his usual self.”

“What kind of unusual is he?”

“You’ll see.” Denise came out from behind the counter and started down a well-scrubbed aisle between examination cubicles separated by curtains. A Spanish-speaking family were clustered in the first one, spilling partly out into the aisle, all of them talking at once. “He’s this way, down at the end. Hardy’s with him.”

“The message I got said your patient didn’t know what year it is.”

“He thinks it’s 1998. To be fair, his memory’s always iffy, so I understand why Hillary thinks I shouldn’t have called you.”

“That’s exactly the sort of memory problem I need to know about. I’ll need to talk to that doctor—the attending?” Lily searched her tired brain and couldn’t come up with the name. “He won’t be happy that you called me, I take it.”

Denise snorted. “Plackett doesn’t want us to take a piss without his say-so.”

In the next cubicle a baby cried, thin and sad, in his mother’s arms. The mother looked about fifteen and exhausted. They passed an emaciated young man with gang tats being hooked up to an IV, an old man on a heart monitor, and a middle-aged couple exchanging worried words in what sounded like Vietnamese.

“I ought to tell you about Hardy,” the nurse went on. “I don’t think there’s anything wrong with his cognition.” Her defensiveness suggested that others did. “But he can’t communicate normally. He was beaten real badly several years ago, see. Brain damage.”

They had to stop and move aside to let an enormously obese woman make her way slowly down the hall with the aid of a walker, breathing heavily. She wore two hospital gowns—one to cover her backside and one her front—and a look of grim determination. As the woman struggled by, music arrived. Harmonica music.

It was a hymn of some sort. Lily knew that much, even if she couldn’t put words to it. Lily had been exposed to religion as a child, but the battle between her parents

over which faith system their daughters would be raised in—Christian or Buddhist—had made her decide to opt out of the whole subject. She’d been studious in her inattention whether dragged to church or to temple, and eventually her parents dropped the subject, too.

The woman beside her obviously recognized the song. She was humming along, smiling. “That Hardy,” Denise said as the obese woman finally passed them. “He can sing most anything—well, old songs, anyway. I never heard him sing any of the newer ones. But he only ever plays the same three hymns on that harmonica of his—‘Blessed Assurance,’ ‘Amazing Grace,’ and ‘In the Garden.’ We hear those over and over. He does a real pretty job with them, though.”

Blessed Assurance. That was what the hymn was called. Mildly satisfied with having put a name to it, Lily followed the nurse to the last cubicle on the right.

The small space held two men. The one in the bed was white, unshaven, and scrawny, with a potbelly and mouse-colored hair. His eyes had the yellow tinge of a failing liver. The one standing beside the bed was over six feet tall and gaunt, though muscle lingered on his wide shoulders. His skin was unusually dark, the kind that takes on a bluish tinge under fluorescent lights, and his hair was grizzled. He wore a faded flannel shirt and baggy gray pants. He, too, could have used a shave.

“This is Agent Yu,” Denise announced. “She’s with the FBI.”

“The FBI,” the man in the bed said in a marveling way. “Imagine that, Hardy. That pretty girl is with the FBI.”

The other man lowered his harmonica to look at her in delighted surprise, as if they were old friends but he hadn’t expected to run into her here. “‘I’ll be calling you . . . ooo,’” he sang. “‘You will answer true . . . ooo.’” His voice was deep and true, but rough. Maybe the beating that damaged his brain had included a blow to his voice box.

“It’s mostly songs with Hardy, see,” Denise said. “Sometimes rhymes, but songs are easiest for him. Music is stored differently in our brains than language, see? He makes himself understood pretty well. Right, Hardy?”

World of The Lupi 04: Night Season

World of The Lupi 04: Night Season World of Lupi 10 - Ritual Magic

World of Lupi 10 - Ritual Magic Mortal Ties wotl-9

Mortal Ties wotl-9 Blood Magic wotl-6

Blood Magic wotl-6 Inhuman (world of the lupi)

Inhuman (world of the lupi) Mortal Danger wotl-2

Mortal Danger wotl-2 Only Human (world of the lupi)

Only Human (world of the lupi) MIDNIGHT CHOICES

MIDNIGHT CHOICES Originally Human (world of the lupi)

Originally Human (world of the lupi) Cyncerely Yours

Cyncerely Yours JACOB'S PROPOSAL

JACOB'S PROPOSAL Human Nature

Human Nature Blood Challenge

Blood Challenge Mortal Danger

Mortal Danger Death Magic wotl-8

Death Magic wotl-8 Blood Magic

Blood Magic Blood Challenge wotl-7

Blood Challenge wotl-7 Dragon Spawn

Dragon Spawn Tempting Danger

Tempting Danger Human Nature (world of the lupi)

Human Nature (world of the lupi) Mortal Sins wotl-5

Mortal Sins wotl-5 Unbinding

Unbinding Night Season wotl-4

Night Season wotl-4 Humon Error (world of the lupi)

Humon Error (world of the lupi) Cyncerely Yours (world of the lupi)

Cyncerely Yours (world of the lupi) Blood Lines wotl-3

Blood Lines wotl-3 Mortal Ties

Mortal Ties MIDNIGHT CINDERELLA

MIDNIGHT CINDERELLA Mind Magic

Mind Magic Human Error

Human Error