- Home

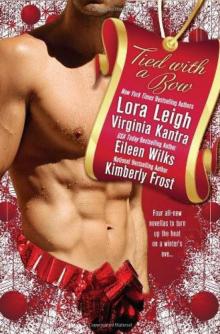

- Eileen Wilks

Mortal Sins wotl-5 Page 9

Mortal Sins wotl-5 Read online

Page 9

“By spiritual shit, do you mean souls? Karonski wasn’t at all sure souls were affected by death magic.”

“Yeah, but Abel is Wiccan. Wiccans focus on this life, not what comes after. They don’t talk much about souls. They don’t really have a theory or dogma about what souls are.”

“I suppose you do?”

“Sure. Your soul is the part of you that loves. Say, what do you think about Daniel Abel?”

The part of you that loves. It couldn’t be that simple . . .

“Lily?”

She tried to remember what Cynna had just said. “What about Abel?”

“Daniel Abel. For the baby’s names. His middle names, that is, because I think kids should have their own first names, but the middle one, that’s a good place to connect him to people who matter. So I was trying to decide between Daniel and Abel, because I’d like him to be connected to my dad, but . . . well, I wouldn’t have gotten straightened out without Abel, you know? Cullen thinks we could give him two middle names. Do you think that’s too much?”

“Two’s okay. You probably don’t want to go for three. What about his first name?”

“Still stuck there.”

“Well, if you do name your baby for Karonski, I want to see his face when he finds out. He’ll melt right down to goo. Listen, I’d better go.”

When Lily put her phone down, she was smiling in spite of the ache that had set up residence at the back of her skull. She glanced at the files, grimaced, and decided to retrieve her laptop before diving in. It was in the trunk of her car.

She needed to make some notes about her discussion with Cullen anyway, so this wasn’t entirely an excuse to get up and move. But it felt good to move, to hurry down the stairs and get a breath of muggy, unprocessed air when she left the building. It would have felt even better to just keep going. She needed a run.

That wasn’t happening anytime soon. In the morning, maybe.

She got her laptop and had just closed the trunk when she heard her name called. Turning, she saw a tall, thin man striding toward her from the far end of the building, his head thrust forward and long, skinny legs covering ground fast, like a stork in a hurry.

Lily sighed. Ed Eames was a reporter with the AP. She’d had some interaction with him in D.C., and he wasn’t a bad sort—the dim, amiable exterior hid a sharp mind and a bulldog’s tenaciousness, but he played fair.

“Can’t give you anything, Ed,” she said when he reached her, and almost managed to sound regretful. “Not even an off-the-record hint. It’s too early in the investigation.”

“Oh, well. Maybe later.” He smiled in that vague way he had. “That wasn’t why I stopped you, though. I’m the one with something to say off the record . . . about Alicia Asteglio.”

TWELVE

WINTER or summer, the backyard was Toby’s favorite place. He loved everything about it—the gazebo, the grass and flowers, the trees. Even when it was real hot, there was lots of shade.

Not that Toby really minded hot weather. Or cold weather, either, from what he could tell, though he hadn’t seen much really cold stuff, not in Halo. Dad said most lupi were like that, not much affected by hot and cold. The magic in Toby was mostly asleep still, but it was there and it had a pattern for him. He sort of leaned toward that pattern even now, years before he could run on four feet instead of two.

Dad started walking along the fence, moving slowly. It felt weird, walking around his yard like this with his dad. Soon this place would be for visits, not really his anymore.

Dad seemed to know that. “There’s a lot here you’re going to miss.”

“Yeah.”

“Make you mad?”

Toby stopped and stared. Sometimes Dad pulled the thoughts right out of his head, like there was a string attached to them he could tug on. “It doesn’t make sense for me to be mad. I want to go. I know it’s right for me to go. So how come it makes me mad when I think about not being here in my yard anymore?”

Dad smiled. “You’ve a strong sense of territory. Most of us do, but it’s stronger in some than others. You’ve been the only wolf here, so this yard is completely yours. It doesn’t matter to your wolf that your grammy is in charge—to him, she’s only in charge of your human self. So this place is yours in a way Clanhome isn’t. Clanhome is your grandfather’s territory—shared with all who are Nokolai, yes, but his. No matter how much you want to be there, you don’t want to surrender what’s yours.”

“Yeah! Yeah, that’s what it’s like. I want to be at Clanhome, but this . . . this is mine. Only how come I feel that way when my wolf’s still asleep?”

“Asleep or not, he’s there. Also, humans are almost as territorial as wolves, so the two instincts strengthen each other rather than competing. Though your wolf’s sense of territory may be somewhat different from your human understanding of it.”

They’d reached the back fence, where Grammy’s azaleas were thick and bushy and smelled so good. “I don’t think I can sort out what’s the wolf and what isn’t. It all feels like me.”

“It is all you. What did you dream last night?”

“Huh?” It took a moment to remember. “I was playing baseball, but there weren’t enough of us on the team and we were losing. The TV people were there ’cause it was a big game, and one of them had a lot of dogs and the dogs wanted to play, too. Grammy said dogs couldn’t play baseball ’cause it wasn’t in the rules, and how would they hit the ball? But you said it was okay, so then the dogs got to be on my team. And then we started winning.”

Dad’s mouth crooked up and his eyes went all pleased, as if that silly dream meant something to him. “The Toby who dreamed about baseball isn’t exactly the same Toby who plays baseball, is he?”

“Oh.” He thought that over. “I see what you mean. When I’m asleep, things seem different from when I’m awake, and I know different things and all. But it’s all me.”

Dad nodded. “For now, your wolf is sleeping so deeply that the awake Toby doesn’t know what the sleeping part knows. It’s like when we can’t remember our dreams—that doesn’t mean we didn’t dream. Just that our dream self is too distant from our awake self for us to claim the memories. After the wolf wakes and you take that form, you’ll remember that part of you all the time. You’ll see many things differently. Some of those differences will be confusing.”

“I know that,” Toby said, impatient. It wasn’t like they’d never talked about this before. “Confusing” meant that when First Change hit, his wolf would be real strong and people would smell like food, so when he was twelve he’d go to terra tradis, where everyone was lupus, so he didn’t hurt anyone. He’d have to stay at tradis after the Change, too, and be home-schooled there, but he’d probably be able to go to a regular high school.

That’s what he planned, anyway. Uncle Benedict said not to count on that. Most new wolves weren’t ready to be around humans all the time, not until they were real old—maybe eighteen. But some of them managed it younger. Dad had. Toby figured he would, too.

They’d finished their circuit of the yard, ending up near the patio. Dad stopped and turned to him. “I told you last night I had some clan business to take care of while I’m here. Because your grammy was present, I didn’t say which clan.”

“Oh. Oh! You mean you have to do Leidolf business? That’s why we’re going there?” Toby’s nose wrinkled. He didn’t like that Dad was connected to the other clan, who had been Nokolai’s enemies forever. Unless . . . He brightened. “Hey! Have you figured out how you can give the new mantle to someone else?”

Dad shook his head. “That won’t happen until the All-Clan.”

Toby didn’t exactly understand mantles yet, but they were sort of like magic blankets covering the clans, keeping everyone steady. It was supposed to be impossible for anyone to carry parts of two mantles, just like it was impossible to belong to two clans. But Dad was doing it.

According to Grandpa, that was the Lady’s doing, and maybe the r

eason for the mate bond between Dad and Lily. Grandpa thought the Lady used the mate bond—which came from her, after all—to help Dad because she wanted the two clans to be friends again. When Toby had asked Dad about that, he’d shrugged and said perhaps. That was one of Dad’s words—perhaps. He used it a lot.

But the Leidolf Rho was real sick and could die, and if he did, the whole mantle would go to Dad. Toby wasn’t sure what would happen then, but it must be pretty bad. No one wanted the whole mantle to go to Dad. Not even Grandpa. That’s why the Rhejes were going to shift it, but they had to all get together to do it, and that wouldn’t happen until the All-Clan, which was months and months away.

“Hey.” Dad ruffled Toby’s hair, then cupped the side of his head. “Don’t look so worried.”

“But if the Leidolf Rho dies and you have to take it all—”

“It will be okay. I’ll be okay, Toby. The Leidolf Rhej is a skilled healer. She’s keeping Victor alive, and I’m careful not to call on that mantle.”

Dad wanted him to feel better, so Toby tried. After all, even if the old Rho died right this minute, Dad had the mate bond, so the Lady could still help him. “You’ll be okay,” he echoed. “But I wish you didn’t have to do Leidolf stuff right now.”

“But right now I do have the heir’s portion, so in all honor I need to fulfill those duties their comatose Rho cannot. Two of Leidolf’s youngsters are ready for the gens compleo.”

Toby didn’t know much about the gens compleo, just that it was when a lupus was accepted into the clan as a full adult. But he knew it involved the clan’s mantle. “They—those youngsters—they’re already in the mantle, though, right? They’re already clan.”

“They’re clan and past First Change, so the mantle knows them, but they aren’t of the mantle yet. That’s what the gens compleo is for.”

That didn’t really explain anything, but Dad said that talking about mantles was like trying to wrap up color in words. No matter how good your words were, they ended up pointing in the wrong direction. He also said that, for lupi, talking about the mantles was like talking about sex used to be for humans—something you did kind of hushed, where others wouldn’t hear.

That had made Toby snort. The grown-ups he knew here in Halo still talked about sex like that. “Hey—you made sure no one was listening, didn’t you? That’s why we went outside and walked around. So you could be sure nobody would hear us, because the mantles are the Lady’s secret.”

“That’s right. We keep many secrets from the humans around us, but only one at the Lady’s behest—the clan mantles.”

Toby nodded. The Lady wasn’t like Santa Claus. She wasn’t like God, either, who you had to believe in, but not everybody did, and even people who did believe argued about Him. But the Lady was real, one hundred percent, and the clans didn’t argue about her because the Rhejes had the memories of what she’d said, only mostly she didn’t talk to them or do much. But sometimes she did. “Lily’s human, but she knows about mantles, doesn’t she?”

“She’s both Chosen and clan. She knows.”

“So the Lady didn’t say humans couldn’t know. Just the out-clan.”

“That’s right.” Dad touched his shoulder, smiling. “You’re full of questions this morning. If I . . . That’s Lily,” he said, and headed for the house.

Toby followed. He hadn’t heard anything. Maybe Dad just picked up that Lily was here? The mate bond let him know where she was, so . . . But it was a more ordinary connection this time, he saw. Dad had his phone up to his ear and was talking, then listening.

It didn’t sound like it was good news. “Shit. Yes, I see. Tell your reporter friend I appreciate the notice . . . No, that won’t be necessary.”

“What is it?” Toby asked as soon as Dad set the phone down.

“I’m afraid reporters are on their way here. They were tipped off about the hearing. I’ll have to talk to them, but you and your grandmother don’t.”

Toby’s heart sped up. “I think I should.”

“No.” Dad headed for the stairs. “Mrs. Asteglio?”

Grammy called back, “Almost finished. I’ll be right down.”

Toby figured he’d better talk fast, ’cause he knew what Grammy would say. “Listen to me! Listen. People like kids. I mean . . .” It sounded dumb when he tried to put words to it, but Toby pushed on. “You’re sort of the image for lupi, right? That’s why you went public and why you do a bunch of stuff, letting people see that lupi are okay. Wouldn’t I make a good image, too? I’m just a kid, but I’ll be a wolf one day, only I don’t look scary or anything.”

Dad stopped at the foot of the stairs. “You’re suggesting you would be good PR for our people?”

Toby nodded. “Humans need to stop being scared of us, right? Well, no one’s gonna be scared of me.” He grimaced. “Old ladies think I’m cute.”

“You’ve a good point, and I’m proud that you’re thinking of our people. However—”

“It’s not the paparazzi, is it? Just regular reporters?”

Dad’s eyebrows lifted. “What do you know about paparazzi?”

“Well, they hounded that poor princess to her death. That’s what Mrs. Milligan says, anyway. And they make up stupid stuff, like that dumb story about your love slaves that was in one magazine next to the alien baby pictures. And they try to take pictures of people when they’re naked.”

Dad’s lips twitched. “Not a bad description. Paparazzi are photographers who . . . you might think of them as lone wolves. A problem on their own, and dangerous when they travel in packs.”

“Rule, a van just pulled up out front. A television van.” Grammy stood at the top of the stairs, looking like she’d bitten into a rotten apple—and meant to spit it out on someone. “How did they find out?”

“That . . . is something I need to explain. Toby.” Dad knelt, putting his hands on Toby’s shoulders. Which made him feel queasy, because it meant he wasn’t going to like what Dad had to say. “I’ve some news that may be upsetting. Lily learned of it from an acquaintance of hers who works for the AP.”

Toby swallowed hard and didn’t say a word, because he knew. The moment his dad said “the AP,” he knew.

Dad’s eyes were angry, but he kept it out of his voice. “Your mother is in town. She’s told the other reporters about the hearing.”

THIRTEEN

THE sharks were circling when Lily pulled to a stop three doors down from the Asteglio house. The press had taken all the closer parking.

But reporters weren’t the only ones on Mrs. Asteglio’s grass. A gaggle of teenagers, several women, a young man holding a toddler on one hip, and assorted sizes of children filled any gaps between cameras, microphone wielders, and the rumpled suits of the print press.

Lily kept her “no comment’s” polite as she threaded her way past outthrust microphones to the semi-safety of the porch. Someone must have threatened them, or they’d have been banging on the door.

The door opened before she could touch the knob. She slid inside, and Rule closed it on the shouted questions.

He was looking especially magnificent. He’d changed into his usual black—black dress slacks, black silk-blend shirt. He wore a pretty dark expression, too, though his voice was mild. “I did say you weren’t to come.”

“I don’t mind well, do I? How’d you get the sharks to stay away from the door?”

“Anyone who comes up on the porch will be asked to leave the property entirely—and so will not be included in the interview I grant the rest.”

“You’re mean. I like that.”

“On the phone you mentioned a problem with the investigation.”

“I’ll fill you in later.” She glanced around.

The foyer opened on the left to the stairs; at the rear to the kitchen; and on the right to a living room that held two sofas and an upright piano. Mrs. Asteglio stood beside the large picture window backing one of the sofas, glaring out at the invaders on her lawn. She was a lanky

woman a little over Lily’s height with gray hair cropped no-nonsense short and pampered skin. Lily had never seen her without makeup and pretty pink fingernails. Today she wore robin’s egg blue slacks with a button-down shirt in a gingham check.

Toby stood a few steps behind Rule, his chin held at a stubborn angle that reminded her of his grandfather, Isen. His eyes were very much Rule’s, though—dark, liquid, hinting at secrets, with the same dramatic eyebrows.

She smiled at him. “Hey, there.”

“Hi, Lily. Tell Dad this is my business, too.”

Lily glanced at Rule, eyebrows lifted, but before he could respond, Mrs. Asteglio announced, “I’m going to go out there and tell them all to go away. They can’t come on private property. Those journalists”—she made the word sound like a curse—“and my neighbors, too, who ought to be ashamed of themselves.”

Rule shook his head. “Your neighbors might leave, but the press will just camp out on the sidewalk and street. The best way to be rid of them is to give them a little of what they want. I’m not the biggest story here, so if I give them a few sound bites, they’ll go back to pestering Lily and the sheriff.”

“And me,” Toby said. “I’ve got sound bites, too.”

“You can just forget that notion, young man,” Mrs. Asteglio told him firmly.

“I need to,” he insisted. “It’s clan business.”

The older woman huffed out a breath. “It’s my grass they’re trampling, my family they want to gossip about, and my daughter who told them about—oh, about your father, and the hearing. Things that should be private. That makes it my business.”

“But Grammy—”

“You want to see yourself on television, but you don’t realize what it would be like, so it’s up to the adults in your life to do what’s right for you. If . . . Rats!”

“Rats” was the strongest expletive Lily had ever heard from the older woman. This time it came in response to the trill of a phone. At least Lily supposed that’s what it was—it sounded like an electronic bird.

World of The Lupi 04: Night Season

World of The Lupi 04: Night Season World of Lupi 10 - Ritual Magic

World of Lupi 10 - Ritual Magic Mortal Ties wotl-9

Mortal Ties wotl-9 Blood Magic wotl-6

Blood Magic wotl-6 Inhuman (world of the lupi)

Inhuman (world of the lupi) Mortal Danger wotl-2

Mortal Danger wotl-2 Only Human (world of the lupi)

Only Human (world of the lupi) MIDNIGHT CHOICES

MIDNIGHT CHOICES Originally Human (world of the lupi)

Originally Human (world of the lupi) Cyncerely Yours

Cyncerely Yours JACOB'S PROPOSAL

JACOB'S PROPOSAL Human Nature

Human Nature Blood Challenge

Blood Challenge Mortal Danger

Mortal Danger Death Magic wotl-8

Death Magic wotl-8 Blood Magic

Blood Magic Blood Challenge wotl-7

Blood Challenge wotl-7 Dragon Spawn

Dragon Spawn Tempting Danger

Tempting Danger Human Nature (world of the lupi)

Human Nature (world of the lupi) Mortal Sins wotl-5

Mortal Sins wotl-5 Unbinding

Unbinding Night Season wotl-4

Night Season wotl-4 Humon Error (world of the lupi)

Humon Error (world of the lupi) Cyncerely Yours (world of the lupi)

Cyncerely Yours (world of the lupi) Blood Lines wotl-3

Blood Lines wotl-3 Mortal Ties

Mortal Ties MIDNIGHT CINDERELLA

MIDNIGHT CINDERELLA Mind Magic

Mind Magic Human Error

Human Error