- Home

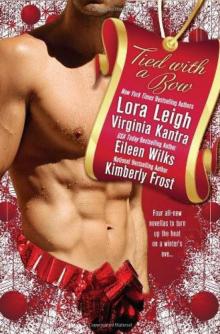

- Eileen Wilks

Humon Error (world of the lupi) Page 5

Humon Error (world of the lupi) Read online

Page 5

Arjenie spoke suddenly. “I bet I can answer the first one. Look at what happened. Something forced you to Change. I bet the twins cast some sort of ‘reveal’ spell—a variation on a truth spell that was supposed to force you to reveal what you really are. Only because they involved Coyote—”

“Raven,” Seri insisted hotly.

“You may have been thinking Raven, but when you tinkered with the invitation, trying to make it not an invitation but something that fit your skewed notion of reality—”

“Skewed? Skewed? Let me tell you, we have been practicing this sort of thing with smaller spells for some time, and results clearly demonstrate—”

“You have, have you?” Robin said softly. “And where have you done this practicing?”

The glance the twins exchanged was easily read by nontwins this time—something along the lines of Oh, shit.

Robin waited. When neither of them spoke, she said, “This is now a coven matter. The family meeting is adjourned.”

“But Mom—”

“Clay?” Robin stood.

He shook his head, but it wasn’t a disagreeing shake. More like resigned and unhappy. Benedict wondered what coven rules the twins had broken and what the penalty might be. “She’s right and you know that. We’ll have to talk with you two privately.”

Robin’s face had gone still, as if she were listening to something. “But not right away,” she said slowly. “We have a visitor, or will very shortly. I believe it’s the sheriff.”

Chapter Six

Sheriff Porter was a tall, ropy man somewhere between fifty and sixty with a luxuriant mustache and a prominent brow ridge overhanging deep-set eyes. Cop eyes, Benedict thought. Like Lily’s. Porter turned down an offer of coffee and asked to speak with Clay and Robin privately.

The house was crowded enough to make privacy difficult to find, so they’d gone out onto the front porch. Everyone else had migrated from the kitchen to the living room; Benedict sat beside Arjenie on the loveseat. He’d considered finding an excuse to linger near the front wall where he’d be able to hear what the sheriff said but decided that might be seen as intrusive.

Arjenie was quiet. He wondered what that family meeting had meant to her. Earlier she’d been angry, but he didn’t think she was angry now. Hurt, maybe, but Arjenie was even worse at brooding than she was at holding a grudge. This seemed to be one of her thinking silences.

“I bet he’s got a case,” Ambrose said. “Don’t you think?”

“Of course.” That was Nate. “We’ve helped out sometimes,” he added directly to Benedict. “The coven, that is. Or now and then one of us is able to lend a hand on our own. Depends on what kind of help the sheriff needs.”

Benedict nodded. The Delacroix family had been here for generations, so they’d had time to build trust both in the community and with the sheriff. Some law enforcement officers refused any sort of magical assistance, but others were more open-minded. And the only magically derived evidence the courts accepted came from certain Wiccan spells. “Arjenie tells me that Robin is a Finder. I imagine she gets called on often.”

“Often enough,” Gary said. “Plus there were those creatures blown in by the power winds at the Turning. A lot of us were involved then, rounding them up, but of course we couldn’t send them back where they belonged.”

“What did you do with them?” Benedict asked.

“The pixies left on their own. No one knows how, but they skedaddled. The gremlins . . . well, not much you can do about gremlins except kill them, but fortunately we just had to find and hold them. The disposal was handled by the FBI’s Magical Crimes Division. The most dangerous one was that snake.”

“Oh man, yeah.” Nate shook his head. “Biggest damn snake I’ve ever seen. At least twice the size of an anaconda, and it could hypnotize its prey, just like they say dragons do. It ate someone, though we didn’t know that until they cut it open.”

“Your coven found and killed it?”

“Trapped it. We avoid killing if possible, especially if there’s some uncertainty about the sentience of the predator. The snake died anyway, though, about three days later. Robin thinks it came from a high-magic realm and there just wasn’t enough here to sustain it.”

Seri grinned. “Or else it ate something that didn’t agree with it.”

“Seri,” Hershey said reproachfully.

She shrugged. “Come on, Uncle Hershey, you know what John Randall was like. Beat that poor wife of his, even if she never would press charges. Too scared, most likely.”

“No one deserves a death like that. Swallowed alive.”

“So it was ugly. So was he.”

Stephen shook his head, his mouth twisting wryly. “You and Sammy didn’t see the body. It’s easier to joke about that sort of thing if you don’t see the object of your humor half digested.”

“You didn’t see it, either,” Seri protested. “You weren’t here during the Turning.”

“True. I saw other things, however.”

That sparked Benedict’s curiosity. Stephen was a wanderer, according to Arjenie. The rest of the Delacroix brothers had settled near their homestead. Hershey and his partner were practically neighbors; Nate and Ambrose were about fifty miles away. Arjenie had moved farther than most, but D.C. was still only two hours from here. Stephen, however, kept a post office box in his old home town but had no permanent address. He traveled all over the country. Why?

“Benedict,” Arjenie said quietly.

He turned to look at her. She had beautiful eyes. Ocean eyes, not blue or green or gray but partaking of all those and varying according to the lighting. Or maybe they reflected her surroundings and her self the way water reflects the mood of the sky . . .

At the moment, they were the color of the sea beneath a cloudy sky. He put a hand on her thigh. “Yes?”

“I’m going to tell them. Not all of them,” she said softly, “but Aunt Robin and Uncle Clay. They need to know, and they’ll keep our secret, just like you’re keeping theirs.”

Shit. She was talking about the mate bond. “We don’t speak of that to out-clan. Ever.”

Her chin came up. “And my family doesn’t talk about the land-tie to those who aren’t coven. Ever.”

He frowned, trying to put into words down why speaking of the mate bond would be wrong when it hadn’t been wrong for Robin to tell him about the land-tie. Which, admittedly, did seem the same, on the surface . . .

Arjenie patted his hand. “Don’t worry. It’s not your decision or responsibility. If Isen wants to yell at me later, he can.”

The front door opened. Clay stood in the doorway. Something about him reminded Benedict of his father and Rho. Isen often stood just like that, his wide stance matching his wide shoulders. He sent a glance around the room. “Robin and I will be going with Sheriff Porter. We’re requesting volunteers, enough for a small circle. Arjenie, Seri, Sammy—we’d like you to participate, an’ you so will.”

Ambrose frowned. “You want the twins instead of me and Nate or Stephen?”

“Trouble’s coming,” Stephen said softly. “If Robin’s going to be off the land for a while, and Clay with her, we need people here who can act, if necessary.”

Ambrose accepted that with a nod. “You’ll have to link us to the wards, Clay.”

“Of course.” Clay looked at Benedict. “Robin explained to Sheriff Porter about your heritage and abilities. If you’re willing, you may be able to help, too.”

That was convenient, since there was no way he was letting Arjenie go without him. He stood. “My men—”

But Clay was shaking his head. “The sheriff is willing to take a chance by including you, but he doesn’t want to be, ah, surrounded by wolves who might not see things his way. They’ll need to stay here.”

Benedict considered signaling Josh that he and Adam were to follow discreetly, but decided to comply with the sheriff’s restriction. They might be needed here. He didn’t know what, if anything, Robin could d

o defensively when she wasn’t on her land, and he and Arjenie would be with law enforcement officers. Not the backup he’d choose, maybe, but they had some training and they’d be armed. “All right. Will I need to Change?”

“No, you’re fine.”

“He means into a wolf,” Arjenie said.

“Oh, ah, I don’t know. Yes, probably. We thought you might be able to track by smell.”

“My other form will be better for that. I should eat something.”

“Ack.” Arjenie popped up. “I’m a bad mate. I should’ve made sure you had something to eat earlier. Uncle Clay, can I dig in the refrigerator for whatever’s defrosted?” She looked at Benedict. “I’m thinking that you eat faster when you’re four-footed, so—raw?”

“Good thinking.”

“There’s not time for a meal,” Clay said.

“We’ll take some meat along,” Benedict explained as Arjenie hurried to the kitchen. “I can eat after I Change. Like she said, I eat fast as a wolf.” He decided they needed more information. “I’ve Changed twice already. The Change makes me hungry. A hungry wolf wants to hunt. My control is excellent, so you needn’t worry that I’d be a danger to you, but hunger would be a distraction for me.”

Clay looked at him a moment, then nodded and raised his voice. “Arjenie? Not the turkey.”

Arjenie had always felt uncomfortable around Sheriff Porter. It was nothing he’d said or done or not done. It wasn’t intuition or distrust or anything like that. It was memory.

Twenty-three years ago, he’d been a deputy. His was the first face she remembered seeing after the accident. She’d been told that she was conscious earlier, that she’d responded to the people who stopped after a drunk drove his pickup into them, but she didn’t remember any of that. She remembered Ab Porter’s face, those deep-set eyes dark and steady as he told her to hold still, hold on, that the ambulance would be there soon and they’d get her fixed up.

He’d been right about that, though it took three major surgeries, a couple of patch-ups, and a whole lot of rehab. And, of course, she was never fully fixed. They hadn’t known as much about growth plate injuries back then as they did now. Her left leg would always be a bit shorter than her right, her ankle a bit weak.

Twenty-three years ago, Deputy Porter had climbed into the backseat with her, using his body to block her view of the front of the car. He’d stayed there until the paramedics arrived, in a position she realized later must have been hideously uncomfortable, given how smashed up the car was. He hadn’t wanted her to see what two tons of truck had done to her mother.

Ab Porter was a kind man, a good man, and she was grateful to him. But she was not quite comfortable with him, so she would rather have ridden with Uncle Clay in the pickup. But when he said the twins would ride with him he used his “don’t argue” voice, which meant he intended to have a talk with them. Arjenie ended up in the back of the sheriff’s car with her aunt.

Benedict rode up front. That was her suggestion, and he’d given her a hard look when she made it because he didn’t like anyone knowing about his vulnerabilities. Not that he was terribly claustrophobic, but neither she nor her aunt was bothered by that sort of thing, so why should he be uncomfortable? The back of the sheriff’s car locked automatically. He’d feel like he was in a cage.

Anyway, she’d just said she wanted to talk to her aunt, so she hadn’t given him away.

“I haven’t met a lupus before,” Porter said as he pulled away from the house, “much less worked with one. I need to know what to expect.”

“First, you should know I’m armed. I have a concealed carry permit from your state. Do you want to see it?”

The sheriff did want to, so they sat there a moment with the dome light on—it was getting too dark to see well—while he inspected it. “What are you carrying?”

“Smith and Wesson .357 chambered with .357 Magnum JHPs.”

In deference to her family, Benedict had left his weapon in their room with his jacket. But when he’d said, “I’ll get my jacket,” and gone to their room, she’d been pretty sure he’d come back wearing more than his new leather jacket. He did not, she noted, mention the knives. He was wearing at least two of them—one in his boot, the other in a belt sheath. Virginia law concerning knives was rather murky, but she suspected neither knife was strictly legal.

“That’s a lot of stopping power,” Porter said, starting the car.

“If something needs to be shot, I want it to stay down.”

Porter grunted. “Resist the urge to use it. I need you for your nose, not your weapon. Robin says you’ll be as good as a bloodhound.”

“I did not say bloodhound,” Robin corrected mildly. “I suspect bloodhounds can outsmell a wolf.”

“Robin’s correct,” Benedict said. “Bloodhounds have extraordinary noses, and their ears and wrinkled skin trap the scent to help them track. But wolf noses are good—somewhere between ten thousand and a couple hundred thousand times as good as a human’s, depending on which expert you listen to.”

Porter nodded. “And you’ll be able to understand us when you’re a wolf? You’ll still think like a man?”

“I don’t think exactly the same way when I’m wolf as I do when I’m man, but I don’t think like a wild wolf, either. I’ll understand you just fine. I’ll know who you are, that you’re the sheriff, and what that means—law, the courts, the whole complex system. But that kind of complexity isn’t interesting to a wolf. I have to make an effort to call up some things. Do you know how to find the circumference of a circle?”

“Ah—something to do with pi. Pi r squared . . . no, just Pi r. Pi times the radius.”

“You had to stop and think about it. That’s what it’s like when I’m wolf. I know the same things, but some of them aren’t at the top of my mind.”

“Huh. Will the need to keep your teeth to yourself be at the top of your mind?”

Benedict chuckled. “Good way to put it. Yes, it will. Some things are . . . if not instinctive, then automatic. Ingrained.”

“It’s like asking an engineer or math teacher about pi,” Arjenie put in. “It would be right there at the top for them, because they work with it a lot and it is interesting to them. The clans train their youngsters really well so that—” No, wait, she couldn’t finish that sentence the way she’d intended. “So that they don’t eat anyone” would not create the right impression.

“So that we understand the difference between people and prey,” Benedict finished for her. “I will no more overlook that difference as a wolf than I would as a man. Nor will I mistake normal human actions for a threat, the way a wild wolf would, or become excited by certain scents.”

Fear, he meant. Wolves could get excited by that smell, but to Benedict it would be information, nothing more.

Benedict paused, then added, “You will find it works better to ask me to do things rather than telling me what to do.”

This time it was Porter who chuckled. “You’re no different from most men, then. People generally prefer being asked. I’ll try to keep in mind that you’re not one of my deputies.”

That made Arjenie grin. Benedict would certainly not look like a deputy.

“That will help. You want me to track someone or something.”

“Something,” Porter said. “Or that’s what we think right now. Some boys—teenagers—found a body down by Moss Creek this afternoon. A man.”

“Oh, no,” Arjenie said. “Do you know who?”

“Assuming the ID in his wallet is accurate, it was Orson Peters. Robin here didn’t think you’d know him.”

She thought a moment, shook her head, then realized he couldn’t see her. “I don’t think so.”

“He’s an ex-con, so I’ve kept an eye on him. Did odd jobs mostly but he kept his nose clean, aside from some trapping I tried not to notice. He lived alone in a little shack not far from where the body was found.”

Benedict spoke. “If you’ve kept an eye on Peters but

couldn’t ID him without his wallet, I’m guessing the body was in bad shape.”

Porter nodded. “Looks like he was mauled by something with claws and teeth, then partly eaten.”

“Which parts?” Benedict asked.

“Why the hell does that—”

“Humor me.”

The sheriff shrugged. “The guts, from what I could tell. Things were pretty much of a mess, though, so don’t hold me to that.”

Yuck. Arjenie looked at her aunt in disbelief. She and Uncle Clay wanted the twins to be part of a circle investigating that kind of ugly? Even if the body had been removed by now—and she was hoping hard it had been—Arjenie would not have brought Sammy and Seri into this. They’d turned twenty a month ago. In some ways they were wise beyond their years, but in others they were naive, even immature. “Uh . . . has the body been removed?”

Porter gave her a look that said he knew some of what she’d been thinking. “Yes.”

“You’ve got an animal attack,” Benedict said, “but you haven’t asked me where I’ve been today.”

“Unless Arjenie wants to contradict what her aunt and uncle told me, you’ve been with her this morning, and with the whole family since you arrived around two. But Peters wasn’t killed today. It’s yesterday and the day before I’m interested in.”

But not worried about, Arjenie thought, or he would have made sure Benedict was sitting back here, safely locked up, when he asked that question. Why wasn’t he worried?

“I was in D.C. We flew in on the nineteenth, arrived at eight forty that night. Stayed at her apartment, which we packed up. Arjenie and my men can speak for my whereabouts the whole time.”

Porter’s eyebrows lifted. “Your men?”

“Josh Krugman and Adam Thorne. Bodyguards.”

“Interesting life you lead if you need bodyguards. I’ll want to talk to them, but later. Your story matches what Robin told me.”

“And that’s enough for you?”

“She also said that you make a very big wolf. A big black wolf.”

Benedict nodded.

“We found a tuft of fur near the body, got caught on some branches. That fur’s kind of an orangey brown, which doesn’t prove anything . . . but we also have some tracks.”

World of The Lupi 04: Night Season

World of The Lupi 04: Night Season World of Lupi 10 - Ritual Magic

World of Lupi 10 - Ritual Magic Mortal Ties wotl-9

Mortal Ties wotl-9 Blood Magic wotl-6

Blood Magic wotl-6 Inhuman (world of the lupi)

Inhuman (world of the lupi) Mortal Danger wotl-2

Mortal Danger wotl-2 Only Human (world of the lupi)

Only Human (world of the lupi) MIDNIGHT CHOICES

MIDNIGHT CHOICES Originally Human (world of the lupi)

Originally Human (world of the lupi) Cyncerely Yours

Cyncerely Yours JACOB'S PROPOSAL

JACOB'S PROPOSAL Human Nature

Human Nature Blood Challenge

Blood Challenge Mortal Danger

Mortal Danger Death Magic wotl-8

Death Magic wotl-8 Blood Magic

Blood Magic Blood Challenge wotl-7

Blood Challenge wotl-7 Dragon Spawn

Dragon Spawn Tempting Danger

Tempting Danger Human Nature (world of the lupi)

Human Nature (world of the lupi) Mortal Sins wotl-5

Mortal Sins wotl-5 Unbinding

Unbinding Night Season wotl-4

Night Season wotl-4 Humon Error (world of the lupi)

Humon Error (world of the lupi) Cyncerely Yours (world of the lupi)

Cyncerely Yours (world of the lupi) Blood Lines wotl-3

Blood Lines wotl-3 Mortal Ties

Mortal Ties MIDNIGHT CINDERELLA

MIDNIGHT CINDERELLA Mind Magic

Mind Magic Human Error

Human Error