- Home

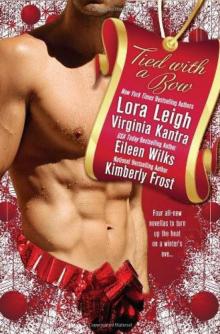

- Eileen Wilks

Blood Challenge Page 23

Blood Challenge Read online

Page 23

Arjenie wanted Benedict. Instead she was stuck with the most gorgeous man she’s ever seen, a man who shared her interest in spellcraft and theory and could discuss them in an informed and intelligent—if occasionally sarcastic—way.

Some might say she was hard to please.

Clearly she was infatuated, but she wanted to see Benedict, talk to him, find out what his father had meant last night, why he didn’t tell people his last name, and what his skin tasted like. Not necessarily in that order.

They were in the den when Cullen steered the talk to her Gift. She told him about the way glass affected it. “The glass in the windows doesn’t bother you?” he asked.

Arjenie was curled into the corner of the big sectional about four feet from where Cullen sprawled in an armchair, and less than ten feet from the windows lining the back wall. “Nope. If I tried to use my Gift, though, it would . . . scratch at me. Interfere.”

“Focus Fire, stop Air, seal Water, open Earth.”

“Exactly. Now, if I were touching glass and pulled hard on my Gift, I’d pass out. So would . . .” Her voice drifted off. She’d seen something move outside. What—oh, it was just a dog. A yellow Lab, she thought. Not a wolf. Not a man who sometimes walked as wolf, either. “So would anyone nearby,” she finished, “if it was a large piece of glass.”

“Who are you watching for?”

“No one. Or, well . . .” She fluttered a hand. “I keep wondering where Isen is. He’s been gone since before I got up, which was about five thirty your time. And you won’t tell me where he is.”

“He has many duties as Rho,” Cullen said blandly. “And he doesn’t need much sleep. Are you sure he’s the one you’re looking for?”

Her cheeks heated. Maybe she’d been a bit obvious about her infatuation. “I guess Benedict has many duties, too. Does he live here? Here in this house, I mean.”

“Here or at the barracks or at his cabin up in the mountains.”

“Those are all places he stays, maybe, but where does he live? Where’s home?”

“You’re thinking like a human.”

“Duh.”

He grinned. “Point is, you think of this house as Isen’s—and it is—but all of Clanhome is Isen’s. Just as all of it, including this house, is ours. The clan’s.”

She frowned. “You don’t draw lines between one person’s property and another’s?”

“We do, but not the way you’re used to. Especially not when it comes to our Rho. He’s ours. We’re his. Everything he owns, we own. Everything we own, he owns.”

Arjenie had known that the clan’s holdings were in the Rho’s name, but she hadn’t grasped what that meant. She didn’t think she grasped it now, either. “Okay, but . . . say you own something and another clansman wants it. Whose is it?”

“Mine. I might decide to give it to him, but it’s my choice. He’s unlikely to ask, of course, because status is involved. Remind me to tell you about the magpie game. Our kids and adolescents love it, and sometimes adults play it, too, though only among close friends. But if the clan itself needs something, then it’s the clan’s.”

The magpie game? She shook her head, determined to stay on topic for once. “And your Rho gets to decide what the clan needs?’

“Of course.”

“What if you’ve got a greedy Rho? One who confuses his own wants with the clan’s needs?”

“A Rho who’s perceived to be taking things selfishly would be Challenged. Eventually he wouldn’t be Rho anymore.”

“How does someone stop being Rho?”

“He dies.”

She shivered. “These Challenges are to the death?”

“They can be.”

“Has Isen ever—”

“No. Not for greed. I haven’t been Nokolai long enough to know that in an absolute sense—internal Challenges aren’t supposed to be spoken of outside the clan, so theoretically it could have happened without my knowing. But I can’t imagine it. Nothing matters to Isen the way Nokolai does. His sons come close, but Nokolai comes first. Whatever Challenges he’s faced, they weren’t because he was greedy.”

“What do you mean, you haven’t been Nokolai long? I thought lupi were born into their clans.”

“Stop asking so many questions.”

She grinned. “Why?”

He snorted. “Back to the way glass affects you. Clearly your Gift is tied to Air. We can’t rely too strongly on human models since it isn’t a human Gift, but it seems that—”

A deep, growly voice spoke. “You’re supposed to be guarding her. I could have taken you both out while you yammered on about Gifts and Challenges.” Benedict stood in the doorway that opened onto the entry hall, his hands on his hips.

Cullen glanced over his shoulder, unruffled. “You could take us both out with or without warning, though I did know you were here. I warded the house last night.”

The funny thing was, Arjenie hadn’t been startled, either. She hadn’t heard the front door open or close. She hadn’t seen Benedict appear in the hall. No, it was as if she’d known Benedict was there. She just hadn’t noticed that she knew until he spoke. “Hi,” she said happily.

Benedict gave her a nod, but spoke to Cullen. “Cynna’s ready to come home. She’s pretty worn-out. This was a hard one.”

Cullen left. He didn’t say ’bye, nice talking to you, gotta go, or anything else. He just left, moving fast. This time she heard the front door open and slam closed. She looked at Benedict. “He’s a sudden one, isn’t he? Though I guess we have to expect that with a Fire-Gifted. Cynna’s all right?”

“She will be. Where’s your cane?”

“In my room. I don’t need it anymore.”

He frowned and started for her. “I need to check your ankle.”

“Ask.”

“If you object, I—”

“Giving me a chance to object is not the same as asking permission. You’re used to telling people what to do. That works with those guards you’re in charge of. You aren’t in charge of me. You have to ask.”

One corner of his mouth turned up. “It’s more efficient my way.”

“If your primary goal in life is efficiency, you should just die.”

That startled him. His head actually jerked back. “What?”

“The most efficient way to live a life is to die a couple seconds after you’re born. Pfft. Done.” She dusted her hands to demonstrate that. “It’s too late for you to achieve optimal efficiency, but you could still . . .”

Benedict was laughing. Silently. She couldn’t hear a thing, but his face, his open mouth, his whole body said laughter. It only lasted a few seconds before dwindling to an audible chuckle. “You have a strange mind. I like it. I like you.”

He sounded surprised. She was surprised, too. Also delighted. And turned on. Her cheeks heated.

“May I check your ankle now?” he asked courteously.

She gave permission, and he knelt in front of her to unwrap the elastic bandage, which made the flutters in her belly worse. The man said he liked her, and she reacted like a tween with a crush. It was almost as mortifying as it was wonderful.

He took her foot in one big hand and rotated it. “Good movement.”

“I want to know who this enemy is Isen spoke about last night.”

“You’ll be told about her, but not now.”

“Why not?”

“I’m taking the day off. Swelling’s gone,” he added, beginning to rewrap the ankle.

“You won’t answer questions because you’re on vacation?”

“More or less.” His mouth turned up wryly, as if at some private joke. He tucked the end in securely. “A brief vacation. One day. How does your ankle feel?”

“Fine.”

His eyebrows lifted. “A one-word answer?”

“I got tired of answering questions about my health twenty years ago.”

“After the accident.”

She nodded.

“I imagine there

was a long recovery and therapy. You mentioned additional surgeries, as well, later on.” He nodded as if he’d added up a column. “I may have to ask about your physical status sometimes, but I’ll avoid it when possible.” He rose. “Today I needed to know because I’d like to show you around Clanhome.”

She beamed. “I’d like that. My ankle really does feel fine. There may be some lingering weakness I won’t notice until I’ve been walking on it awhile, but Dr. Two Horses’s treatment helped, plus I heal faster than most.”

His eyebrows lifted. “The sidhe blood?”

She nodded. “Obviously I don’t always heal completely, or at the rate your people do. But I heal fast for a human.”

“I’ll get your cane.”

“I’m not taking it.”

“It’s a precaution, in case you need it later.”

She stood and patted his arm reassuringly and smiled. “No.”

TWENTY-FIVE

THE cane stayed behind.

Benedict worked this out logically. If he brought it along after that firm refusal, she’d be annoyed and more determined than ever not to use the thing, even if she needed it. More important, though, it was the wrong thing to do. Children needed to have limits set for them. Arjenie wasn’t a child. She was his to protect, but not from herself. Not from the consequences of her own decisions.

That was the problem.

He’d dreamed of Claire last night. Once that had been common, but not these days. Still, he supposed it would have been more surprising if she hadn’t shown up. In the dream, he’d been at his cabin, which had mysteriously sprouted a new room. A bedroom. Arjenie had been asleep in the new bedroom when Claire walked in.

Sometimes his subconscious was damned unsubtle. “I thought we’d look in at the center first,” he said as he and his new Chosen left his father’s house.

“What’s that?”

“Our child care and community center. We don’t get cable out here, so there’s a satellite dish and a big-screen TV at the center for those who want to watch HBO or Showtime.” He glanced at her. “But maybe you knew about that.”

Arjenie looked apologetic. “The satellite dish does show up on aerial photos. So does the playground equipment. But, um, I haven’t seen inside your center.”

“Nice to know a few things aren’t in the government’s files. We’ll go to baby room first,” he said, opening the front door and stepping out ahead of her. The human courtesy of waiting for the woman to go through a door was all flourish, no sense. If any danger waited on the other side of a door, he’d rather meet it himself, not send her into it.

“Baby room?”

She was moving easily, he noted. Just as she’d said, her ankle wasn’t bothering her. He kept his pace slow. “Where the tenders mind the clan’s babies. Any who are here, that is. Obviously a lot of them won’t be. Even when the father has or shares custody, he may not live close enough to use the center regularly.”

She nodded seriously. “The courts haven’t been exactly friendly to lupus dads. I know Mr. Turner—Isen’s son, I mean, Rule Turner—wasn’t able to have custody of his son until recently.”

Rule’s custody hearing had made headlines—especially since it coincided with a string of supernatural murders. “Some mothers won’t share custody with a lupus father, and until recently there was no chance of pursuing legal remedies. Still not much point in it, in most places. And many of the mothers who do share custody live too far away for their babies to be tended here when they’re at work.” Of course, some women—like Rule’s mother—handed their babies over to their lupus fathers as fast as they could. They didn’t want a child who was going to turn furry one day.

The gravel path didn’t seem to be giving her any trouble. “If I understand correctly,” she said, “that would be girl babies and boy babies both, right? You consider your female children part of the clan even though they can’t Change.”

They also couldn’t be included in the mantle, but he wasn’t going to explain mantles yet. “Is that in the FBI’s files?”

“Well, yes.”

“Your file’s right. Our daughters are clan. Their children aren’t, but are considered ospi, or friends of the clan. Several of the babies and younger children at the center are ospi.”

“You provide child care for them, too? Even though they aren’t clan?”

“Babies are babies.” It was beyond Benedict’s understanding that, in the human world, there were children who went unclaimed, unwanted. Logically he could see that a race as astonishingly fecund as humanity could afford to be careless with its young, but everything in him revolted at the idea.

To be fair, many humans were revolted by it, too.

She fell silent as they reached the road that circled the meeting field, a grassy swathe that anchored the little village at Clanhome’s heart. The center was about two miles away, on the southeast corner of the meeting field; Isen’s house was at the northern end, banked up against the mountains.

It was a typical fall day for their corner of the county—sunny and warm, the sky blue enough to raise an ache in the heart, spotted here and there with puffs of white. A breeze tugged at Benedict’s shirt sleeves and tangled itself up in the riot of Arjenie’s hair. She’d left it down today, and it shone in the sun like molten copper.

The wind smelled of cholla and pine, rabbit and dirt . . . of home.

It was good to be walking here on this hard-packed dirt road, smelling home and feeling the sun’s warmth. Good to be alive to feel these things. Even after the overmastering pain had subsided, it had taken him years to be able to feel that simple joy, untainted by guilt. How, he had wondered, could he exult in life, when Claire would never feel these things again?

He’d finally understood that his grief and guilt added nothing to the short span of Claire’s life. He’d had the question backward. The real question was: How could he not?

He was glad now that he’d lived. Life wasn’t a burden taken up because his Rho insisted he was needed, and it hadn’t been for a long time. Life was what it was. Short or long, bitter or sweet, life simply was.

As Claire had reminded him tartly last night. Quit feeling sorry for yourself, she’d said. Good God. What’s so special about pain? About fear? You know fear. Even back when we were together—and you know, you really weren’t that bright about some things back then—you understood fear better than me. I went crashing around, smashing into everything so I wouldn’t have to face my fear. You told me then I had to face it, accept it.

She’d snorted. It had sounded just like her, too. Some reason you want to make my mistakes instead of finding one of your own?

Smart Claire.

Maybe it really had been her he spoke with in the dream, not just the promptings of some buried, wiser self. Maybe not. Benedict knew there was something beyond death. He didn’t know if that something allowed a woman who’d been dead for forty-two years to drop in on him in his sleep. It seemed possible. And impossible to know for sure.

And it didn’t matter. Benedict drew a deep breath, looking around at so much that he loved . . . none of which was guaranteed to last until tomorrow. He’d lay down his life to make it last, if necessary, but even then he didn’t get any guarantees.

Fear could be helpful, if you learned the right things from it. Or it could make you helpless. He was tired of being helpless. “You’re quiet,” he said to the woman walking beside him. Walking, not limping.

“Every now and then,” she agreed. “It doesn’t happen often, but now and then I stop talking. I was wondering . . . you said you were a father.”

“Yes.” He might as well tell her. She would be learning a great many of their secrets. “What did you wonder?”

“Pretty much everything. Do you have a son or a daughter? Will we see him or her at the center, or is your child older, or not living nearby? What about the mother? Do you have custody, or . . . you’re laughing at me.”

Yes. Yes, he was. That felt good, too. �

��You’ve kept a lot of questions pent up.”

“I was waiting for you to finish that thinking you were doing. It seemed to be making you feel better. Lighter.”

He cocked his head, curious. Most people couldn’t read him at all. Especially humans, who couldn’t use scent as a guide. “It did. I have one child, a daughter. Nettie Two Horses.”

For some reason, that delighted her. “The doctor who treated me is your daughter?”

He nodded. “You may be surprised by her appearance when you meet her.”

“She doesn’t look like you?”

“Around the eyes she does. She’s got her mother’s chin and jaw, and her mouth is a feminine version of Isen’s. But that wasn’t what I meant.” He paused. “She’s fifty-two.”

She blinked. “Oh. Oh! I was right! You don’t age the way humans do.”

He stopped, staring. “You know?”

“I didn’t know until you said that, but I guessed. I mean, it’s logical, isn’t it? If you heal damage almost perfectly, you’d heal free radical damage, too, so you’d age more slowly. Oh! Is that why you don’t use your original surname? Because it might give away your real age?”

Urgently he said, “Does the government—”

“No, no.” She patted his arm reassuringly. “That isn’t in any of the files I have access to. And I access Restricted and Confidential information routinely, and am cleared for Secret if I jump through the right hoops, and even Top Secret with specific authorization. Generally, if I run across a pertinent reference that involves Top Secret material—some of the Secret files are heavily redacted Top Secret material—I simply annotate it to that effect, and the agent making the inquiry can either request the complete file or not. But I’ve read pretty much everything the Bureau knows about your people. That information isn’t in the files.”

He wasn’t reassured. “Who have you told?”

“No one. Like I said, I was just guessing, and I understand the need to keep some things secret. Even basically nice people might start envying lupi your longevity, and envy can be extremely toxic. Though I don’t think you’ll be able to keep it secret forever.”

World of The Lupi 04: Night Season

World of The Lupi 04: Night Season World of Lupi 10 - Ritual Magic

World of Lupi 10 - Ritual Magic Mortal Ties wotl-9

Mortal Ties wotl-9 Blood Magic wotl-6

Blood Magic wotl-6 Inhuman (world of the lupi)

Inhuman (world of the lupi) Mortal Danger wotl-2

Mortal Danger wotl-2 Only Human (world of the lupi)

Only Human (world of the lupi) MIDNIGHT CHOICES

MIDNIGHT CHOICES Originally Human (world of the lupi)

Originally Human (world of the lupi) Cyncerely Yours

Cyncerely Yours JACOB'S PROPOSAL

JACOB'S PROPOSAL Human Nature

Human Nature Blood Challenge

Blood Challenge Mortal Danger

Mortal Danger Death Magic wotl-8

Death Magic wotl-8 Blood Magic

Blood Magic Blood Challenge wotl-7

Blood Challenge wotl-7 Dragon Spawn

Dragon Spawn Tempting Danger

Tempting Danger Human Nature (world of the lupi)

Human Nature (world of the lupi) Mortal Sins wotl-5

Mortal Sins wotl-5 Unbinding

Unbinding Night Season wotl-4

Night Season wotl-4 Humon Error (world of the lupi)

Humon Error (world of the lupi) Cyncerely Yours (world of the lupi)

Cyncerely Yours (world of the lupi) Blood Lines wotl-3

Blood Lines wotl-3 Mortal Ties

Mortal Ties MIDNIGHT CINDERELLA

MIDNIGHT CINDERELLA Mind Magic

Mind Magic Human Error

Human Error