- Home

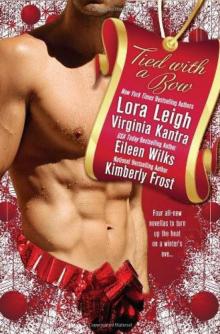

- Eileen Wilks

Blood Challenge Page 12

Blood Challenge Read online

Page 12

“We’ll call soon. We’re going to move you now.”

“O-NEGATIVE.” Lily lay on a gurney in the back of the ambulance. The motor was idling, the siren silent. Up front, a door slammed as the driver got in. “And that’s all you get until you call.”

“Special Agent,” Brown-and-brown said, “no doubt you are used to being in charge. You aren’t in charge now. I said I’d call, and I will—after we reach the hospital. Now you need to answer some questions. Any allergies?”

Lily set her jaw and stared at the ceiling. It was way too close. Everything was too close and cramped in the back of an ambulance. Rule would hate it.

“I need to know if you’re allergic to any drugs.”

They pulled away from the curb. Just as Lily thought maybe they’d spare her the siren, it came on. She winced. It probably wasn’t as loud in here as outside, but that urgent blare made her heartbeat jump back into double time.

They’d bound her arm. The pressure was necessary to stop the bleeding, but God, it hurt. No more dizziness, though, thanks to the IV now dripping fluid into her vein, so she tried to get her brain working.

It was not, she thought, a professional hit. A pro would have used a rifle or an automatic. It clearly hadn’t been an automatic—she was too alive for that—and it had sounded like a pistol, not a rifle.

Brown-and-brown sighed and surrendered. “All right, I’ll call. What did you say his name was?”

“Rule. Rule Turner.”

VANDERBILT had the closest ER, barely five minutes away. That was irony, not a coincidence; Ida had booked them into the Doubletree precisely because it was close to the hospital.

Brown-and-brown hadn’t been able to reach Rule, but she’d left a message. She’d called Croft, too, just as the ambulance pulled into the emergency bay. She hadn’t let Lily speak to him, but at least she’d called. Lily made sure she told Croft about LeBron.

Not Rule, though. He shouldn’t learn that from voice mail.

Many painful minutes had since passed. Lily’s time sense was too skewed to guess how many. Time enough to cut away her top, though it was obvious her only damage was to her arm. Time enough to steal more of the blood they said she was low on. Time enough to get X-rays, during which she’d passed out again, but not, she thought, for very long. They’d followed that up with a CT scan.

Now she lay flat on a hard treatment table, enveloped in pain. Her own fault, she supposed, for refusing pain meds. But she couldn’t turn loose yet, couldn’t . . . only she was tired. So tired.

Still, she tried to pay attention to the doctor who was telling her a great many important things involving her tibia. Or was it her fibula?

No, neither of those were right. Her arm, anyway. Her arm was screwed up. Hollow-point bullet, most likely. They really tore things up on their way out. Like LeBron’s eye socket, exploded into obscene red jelly . . .

“. . . very fortunate there is no significant vascular damage, so we won’t need a vascular surgeon. The surgery may take awhile, given the shattering of your humerus—bone fragments, you know. Got to chase down as many of them as we can, but we have an excellent orthopedic surgeon. He’ll be here very soon, and he’ll take good care of you,” he told her, hearty in his reassurance. “Do you have any questions?”

“Not going into surgery yet.”

The ER physician was a portly man with twin patches of sandy hair in parentheses around his ears. He had a mole just under his chin and a shiny head. He frowned at her in disapproval. “You need surgery, young lady.”

Lily gritted her teeth at the “young lady.” “I’m not refusing treatment. Just not yet. He’s almost . . .” No, wait, she wasn’t supposed to say that. “I need to see him first.”

“He? Who do you mean?”

There was no door to her treatment cubby, so she heard the commotion in the hall clearly. First a woman’s voice: “Sir! Sir, you can’t go—”

Then a wonderful voice. “No, now, you’ll have to get out of my way. My nadia is in there.”

“Visitors are not allowed for that patient—sir! Security! Stop him!”

Relief rolled over Lily in a huge wave. “That’s him, and you’ll let him in here or I swear I’ll get up off this goddamned table and go out there to him.”

“The officers left word that you—”

“I am a goddamned officer, and I say . . . oh. Oh, there you are.”

Rule appeared in the doorway, his hair disheveled, his eyes frantic. “Lily.”

From behind him another man spoke. “All right, you! Hands up and step back. Step away from the door.”

Rule didn’t move, and he didn’t look away from her. “I suggest you put that gun up before you hurt someone.”

“Harvey,” the doctor said, turning, “don’t be waving that gun around. It’s all right. My patient knows this man—whoever he is—and she is not going to cooperate until she sees him.”

Harvey started arguing. The doctor started for the hall. Rule stepped aside for him politely—and came in. Came to her.

“Lily.” He swallowed and touched her cheek so carefully, as if he feared even that might hurt.

She seized his shirt with her good hand and pulled him to her. He let her, and at last, at last she could bury her face in his shoulder, his shirt wrinkled and soft, his scent filling her. At last she could let go. Rule was here.

A shudder hit like a small quake. “LeBron is dead.”

“I know.” He stroked her hair. “I was still four-footed when the mate bond yanked at me—”

It did?

“—so I raced back to the car, Changed, and got that message from the paramedic.”

“But she didn’t say—”

“I called Croft. He told me.”

Her hand clenched in his shirt. “He died for me. He wrapped himself around me and took the bullet. For me.” The first sob shook her, shocked her, sent a white bolt of pain shooting from her damaged arm . . . but that didn’t stop her.

She wept.

THIRTEEN

THE moon’s lumpy face beamed down on the land in its remote, silvery way, making Arjenie think of that “from a distance” song. Maybe things on Earth looked just fine from 238,857 miles away.

Actually, it was closer to 233,814, though that figure might be imprecise. She’d done the calculation herself a couple years ago because the other figure was the center-to-center distance between Earth and its satellite, and she’d been curious about the surface-to-surface distance. She’d used the equatorial dimensions of both bodies to keep things simple, so . . .

So she was distracting herself with trivia again. Not that the distance between Earth and the moon was trivial, but it was not relevant.

Arjenie took a deep breath and opened her car door. The dome light did not come on, and she congratulated herself for remembering to remove the bulb. Lights could be seen much farther away than her Gift could operate, which was why she’d driven the last few miles without headlights.

Tonight’s mission would not be nearly as scary as visiting Dya had been, she assured herself. This time the worst-case scenario didn’t involve anyone killing her.

Though it might involve someone seeing her. She hoped—no, she believed, as firmly as she could manage—that last night’s big, beautiful wolf had gotten away unscathed. Which meant he might be around to see her tonight. Which would be bad, but much better than him not being around at all anymore.

All that determined believing contributed to her thudding heart as she grabbed the tool belt she’d bought that afternoon and got out.

The tool belt went around her waist—or her hips, really, since even the smallest size was a bit large for her. She wiggled her hips, making sure nothing clinked or rattled. Then she reached into her left pocket and withdrew the smaller vial.

It held a tablespoon of clear liquid. Arjenie tugged off the stopper and downed that tablespoonful in one gulp. No taste, no scent—it was like thick water.

She didn’t experie

nce a thing. Dya had told her she wouldn’t. Still, she lifted an arm and sniffed her hand, then under her arm. No change that she could tell. She’d just have to trust that the potion did what Dya said it would. Her Gift would let her go unnoticed, but she needed the potion to keep from leaving her scent on things.

Then she reached into the car for one last tool: a cane.

Arjenie hated the cane. She had one at home, but it spent almost all the time in the back of her closet. She’d long since resigned herself to the clunky orthopedic shoes, but the cane felt like an accusation, an exclamation point at the end of Oh, no, I did it to myself again! But her ankle hadn’t stopped aching since she took that tumble last night. She’d kept it elevated, she’d used a healing cantrip, she’d alternated hot and cold packs. Still it complained, even when wrapped snugly in an elastic bandage.

Unfortunately, she couldn’t wait for it to quit fussing. Her life might not be on the line, but other lives were. That’s what Dya said, and Arjenie trusted her. Not that she thought Dya had been utterly and completely honest. Arjenie suspected Dya’s life was more at risk than she admitted, and there was so much Dya hadn’t told her. But Dya wouldn’t trick her.

Sometimes the best outcome was no noticeable outcome at all. She’d go in, do what she came here for, and nothing would happen.

With that goal firmly in mind, Arjenie and her cane and her complaining ankle set off down the road to Nokolai Clanhome.

The road hadn’t been resurfaced recently, and that was a blessing. The gravel was mostly packed into the ground. She still made some noise as she walked, but hopefully anyone close enough to hear would be within range of her Gift. But lupi hearing was terribly acute. She didn’t know precisely how acute because they’d never let anyone study them that way—and she couldn’t really blame them, given the history between lupi and humans. But it would be interesting to find out.

Only not tonight. Tonight she’d settle for ignorance on her own part as long as it meant ignorance on their part, too.

The air was crisp, the sky cloudless, and her ankle hurt.

Two miles. That’s not so far, she told herself. She might be clumsy, but she was fit. Two miles to the entrance, then another mile or so to her target. If she hadn’t turned her ankle last night, that would be a breeze. It was still doable. Pain was a familiar sparring partner. It might make her cry, but it didn’t stop her.

She was a little worried about the walk back, though.

Nokolai Clanhome covered three hundred forty-nine acres of rough terrain. Fortunately, she didn’t have to hike up and down all that terrain. The road ran right up to her target. Unfortunately, she couldn’t just drive up. Even if her Gift were strong enough to make an entire car impossible to notice, the glass in the windows would blow that plan. Glass impeded magic—Arjenie’s magic, anyway.

Focus Fire, stop Air, seal Water, open Earth. Her feet kept time with the little ditty she’d learned when she was five years old.

Like many mnemonics, it wasn’t strictly accurate. Useful when one was first learning the Craft, she supposed, but not accurate. Glass did magnify some aspects of Fire magic, like precognition, which was sometimes linked to Fire. Some practitioners with that Gift found crystal balls helpful in clarifying the information they received. But others didn’t, and some types of Fire magic were unaffected by glass. Uncle Hershey said glass had no impact either way on his ability to call fire.

Then there was Air. Arjenie’s Gift was tied to Air, and glass didn’t stop her magic. It interfered. The closer the glass, the greater the interference. If she used her Gift while standing right next to a window, for example, she’d get a dreadful headache and lousy results. If she were foolish enough to use her Gift while actually touching a big plate glass window, she’d black out.

So would anyone within twenty feet of her. She knew that because she was foolish sometimes . . . but she’d wanted to know. And she’d only tried it that once.

The mnemonic was right about Earth and Water, though. Glass was open to Earth magic—it had no effect at all. And glass did seal Water. That’s why most potions were kept in glass bottles. Potions drew on lots of different energies, but they used Water magic to hold their action in potential.

Arjenie’s fingers brushed the lump in the pocket of her jacket. The reminder of Dya made her heart ache and started her mind down another worry-path.

Arjenie did not understand Binai ethics, but she knew contracts were their high holy writ. Violations of contractual obligations were far more serious than, say, killing someone you didn’t know. Killing a relative was murder, but otherwise, the morality of murder depended on the context—and the contract.

Dya was risking a contract violation by sending Arjenie here. She said Friar was violating Queens’ Law. Normally Queens’ Law only applied to the sidhe realms, not to Earth—but Dya said it applied to her even here because it was in her contract. She could not be tasked with or coerced or tricked into violating Queens’ Law.

Robert Friar had tricked her. Maybe. Probably.

Dya had overheard something. That’s all Arjenie knew, but whatever Dya had heard, it had shaken her badly enough to risk breaking contract. Of course, if she was right, Friar had already broken contract and she was off the hook on that score. Breaking Queens’ Law invalidated any contract.

Queens’ Law. The words sent cold tingles along Arjenie’s spine. Dya had reason to be shaken, and Arjenie had reason to be hobbling down a dark road well after midnight, doing who knew how much damage to her ankle.

Arjenie was leaning on the cane a lot more by the time she neared the gate. It was the kind made from pipes, and it was closed. Beside it stood a young man in cutoffs with a rifle slung over one bare shoulder.

Arjenie took a deep breath, pulled harder on her Gift, and kept going. The young man didn’t notice her, not even when she climbed up awkwardly on the gate, careful not to let the tools in her tool belt clang against it. Her Gift would probably keep him from noticing sounds, but probably wasn’t good enough.

She swung a leg over and clambered back down. Success. She grinned at herself, at the young man who didn’t know she was there, and limped forward.

A wolf stepped out of the scrub beside the road. He looked right at her.

Arjenie froze. He was much more silvery than last night’s wolf. And he wasn’t looking at her, she realized with a rush of relief. In her direction, yes, but his gaze was focused a little to one side. Maybe at the guard?

Still, she didn’t move as he trotted up the road toward her . . . and on past. Her heart pounded so hard she was almost sick from it. But he did pass.

She looked over her shoulder, curiosity temporarily defeating fear. Sure enough, the wolf went right up to the young man, who made some kind of sign with his hands. The wolf shook his head. The man made another sign. The wolf nodded and set off along the fence.

Whew. Dya’s potion must have worked. Obviously she hadn’t left any scent on the gate.

Arjenie’s hands were shaking as she started moving again. Maybe not just her hands. Excess adrenaline was a lot like sheer terror in that way.

The rest of her mission was anticlimactic. She didn’t see anyone as she trudged down the road, and the only wolves she heard were yodeling at each other up in the mountains. The cluster of houses and a few commercial buildings that she thought of as Nokolai Village lay about three miles beyond the gate, but her target was quite a bit closer. There was one largish dwelling she’d have to pass, however.

The largish building was dark when she reached it, as it should be at this hour. Her heart beat a little faster as she walked by, but no one stirred. About forty feet beyond it she spotted the twin ruts of the trail she needed.

In the end, she didn’t need any of the tools she’d brought, not even the penlight. She had unusually good night vision, and with the moon so near to full she had no trouble finding the wellhead.

Nokolai had multiple wells—probably three, according to the expert she’d cons

ulted. She’d only had time to locate the most recent well, drilled after the state began requiring permits. But Nokolai had a large water tank, easily spotted on the aerial photos. That tank supplied the forty-two houses and six other buildings in its central village. It, in turn, was supplied by all the wells.

In other words, she didn’t have to find and dose all the wells. Whatever she put in one would mingle with water from the others before reaching the houses.

Had the man Friar sent here emptied his vials into a single well, or had he poured them into the water tank? It probably didn’t matter, but she’d never been good at not thinking about something once it caught her interest. Friar’s agent had had a potion like hers to nullify his scent, but he couldn’t have gone unseen the way Arjenie did. There was no such thing as an invisibility potion. How had Friar’s agent snuck around without being spotted?

Very likely he’d put the potion in one of the other wells, she decided. This one would have been hard for him to reach without being seen, and the tank was way too exposed. But he’d had a lot more time than she had to do his research. He’d probably found a well he could approach more secretively.

She lowered herself to the ground beside the wellhead. Her ankle throbbed once, hard, as if surprised by the sudden lack of weight grinding down on it. Then the pain gentled. She smiled in relief.

The cap was right where she’d been told it would be, sticking out of the seal. “People have to chlorinate the water, yaknowwhatImean?” the driller she’d spoken with had told her. That’s how he said it, with the words melted into a single blob. “Got to keep it simple for folks, yaknowwhatImean? Unscrew the cap, pour in the chlorine. That’s it.”

Sure enough, that’s all Arjenie had to do. Unscrew the cap, pour in the potion.

This potion was in a larger vial. There was roughly a cup of highly viscous fluid, more like a murky gel. Arjenie’s human nose picked up a faint scent when she removed the stopper. Something similar to cloves, yet not cloves.

World of The Lupi 04: Night Season

World of The Lupi 04: Night Season World of Lupi 10 - Ritual Magic

World of Lupi 10 - Ritual Magic Mortal Ties wotl-9

Mortal Ties wotl-9 Blood Magic wotl-6

Blood Magic wotl-6 Inhuman (world of the lupi)

Inhuman (world of the lupi) Mortal Danger wotl-2

Mortal Danger wotl-2 Only Human (world of the lupi)

Only Human (world of the lupi) MIDNIGHT CHOICES

MIDNIGHT CHOICES Originally Human (world of the lupi)

Originally Human (world of the lupi) Cyncerely Yours

Cyncerely Yours JACOB'S PROPOSAL

JACOB'S PROPOSAL Human Nature

Human Nature Blood Challenge

Blood Challenge Mortal Danger

Mortal Danger Death Magic wotl-8

Death Magic wotl-8 Blood Magic

Blood Magic Blood Challenge wotl-7

Blood Challenge wotl-7 Dragon Spawn

Dragon Spawn Tempting Danger

Tempting Danger Human Nature (world of the lupi)

Human Nature (world of the lupi) Mortal Sins wotl-5

Mortal Sins wotl-5 Unbinding

Unbinding Night Season wotl-4

Night Season wotl-4 Humon Error (world of the lupi)

Humon Error (world of the lupi) Cyncerely Yours (world of the lupi)

Cyncerely Yours (world of the lupi) Blood Lines wotl-3

Blood Lines wotl-3 Mortal Ties

Mortal Ties MIDNIGHT CINDERELLA

MIDNIGHT CINDERELLA Mind Magic

Mind Magic Human Error

Human Error